Header Image: NYC Department of City Planning // Artist: Alfred Twu

Authored by Benjy Ross, PCAC Intern

An Analysis of How City of Yes Will Enable the MTA to Improve Transit Citywide

The New York City Council has passed City of Yes. What does that mean for the future of transit riders?

City of Yes for Housing Opportunity (City of Yes) is a landmark rezoning law. But it’s more than that. It presents an unforeseen boon for the city’s subways and bus operations to the tune of up to $309 million a year. It will enable the construction of tens of thousands of new units of housing in New York City by updating, for the first time since the 1960s, the ancient and restrictive zoning text in the New York City Charter that governs the density and design of new construction. By permitting a little more housing, including affordable housing, in every neighborhood, the City of Yes proposal has the potential to address New York City’s longstanding housing crisis – making the housing market more affordable and flexible to meet New Yorker City’s needs.

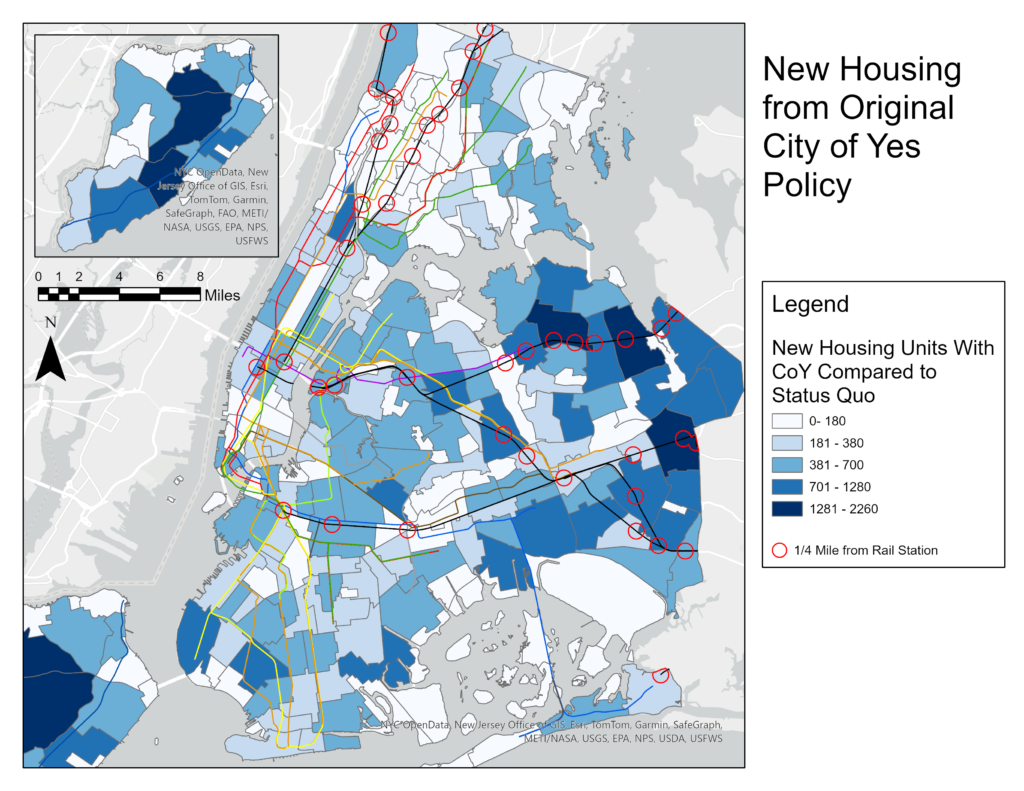

City of Yes reduces or eliminates parking mandates for new construction in most areas, permits transit-oriented development within a quarter mile of rail stations, allows homeowners to construct accessory dwelling units if they choose within designated areas, and makes it easier to construct housing on top of low-density commercial development. The Department of City Planning (DCP) estimates that this policy would result in 58,000 to 80,000 new housing units, up to 22,000 will be affordable, in New York City by 2039 compared to the status quo.

City of Yes Opens the Doors for Better Transit

In addition to making housing more accessible, City of Yes also has the potential to improve and fund New Yorkers’ transit.

By increasing housing supply throughout the city, especially housing developments that include more homes instead of parking, an estimated 70,000 to 97,000 new riders could take the subways, buses, and rails every day. New riders mean additional fare revenue, which would support the MTA’s operating budget.

Given the additional projected ridership, City of Yes could generate an additional $224,188,000 to $309,224,000 every year for the MTA’s operating budget through new fare revenue by 2039. Increased ridership and the revenue it creates helps support service frequency and reliability, and a natural extension should be that people who commute using transit should expect better, more frequent service at their subway, train, or bus stop if they live in neighborhoods that see an increase in housing due to City of Yes.

While it represents only a 2% increase from the MTA’s 2023 operating budget, $309 million could be used to cover labor and other costs of providing service improvements to specific lines or in neighborhoods that direly need improvements, as fare box revenue is dedicated to the MTA’s operating budget. DCP even suggests in their final environmental impact statement (FEIS) for City of Yes that “one of the basic ways to manage increased ridership is to increase the frequency of service during peak times.” To adequately prepare for an influx of new residents in parts of the city, PCAC recommends monitoring ridership changes and deploying gained fare revenue to enhance MTA services whenever possible.

Given the additional projected ridership, City of Yes could generate an additional $224,188,000 to $309,224,000 every year for the MTA’s operating budget through new fare revenue by 2039.

An increase in the MTA’s operating budget could be utilized to improve the transit rider’s experience in many different places. From reducing debt service, to increasing bus frequencies via hiring more bus drivers, improvements to the riders experience have costs that could be covered by new ridership. When riders pay their fare, it allows the MTA to provide service; an extension is that more revenue can equal more service. More people living in housing that makes mass transit convenient should translate to increased ridership for the subways and buses.

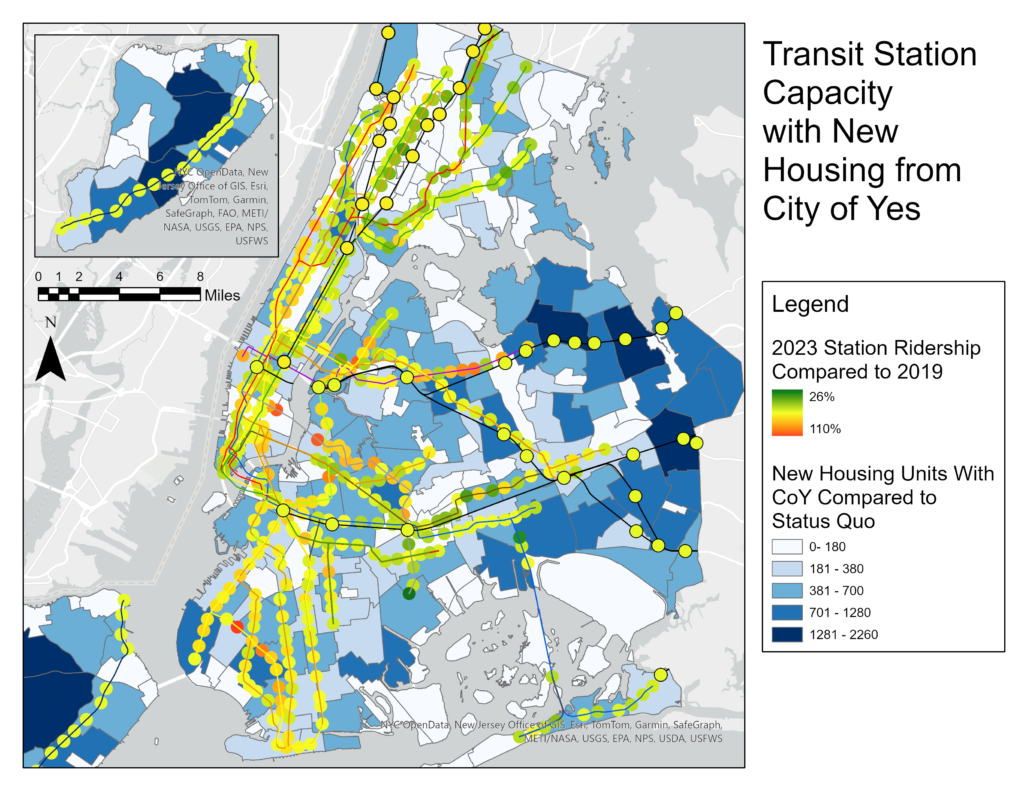

The MTA’s capacity for additional riders

PCAC analyzed post-pandemic ridership on the subway and railroads and found that while ridership has rebounded strongly since the early days of the pandemic, the vast majority of stations and lines see significantly fewer daily passengers in 2023 than they did in 2019. Notable exceptions to this fact include the 7 and L lines, which are running over 2019 levels at many stations and the N and 1 lines, which are near 2019 levels at some stations. The other lines have sufficient capacity to accommodate more people in the future, including the expected increase in passengers due to City of Yes. Increases in ridership will be accompanied by additional fare revenue – even on lines with capacity – making them ripe for additional service to make help them attractive destinations for new homes.

Nearly every neighborhood in the city should expect more housing, in varying degrees. However, neighborhoods in the periphery of the boroughs, such as those in the northern Bronx, eastern Queens, southern Brooklyn and Staten Island are expected to see a greater increase in housing relative to other neighborhoods due to their current relatively low housing density. The subway stations that serve these neighborhoods are also the stations with some of the lowest ridership compared to 2019. There is ample capacity at these stations to serve the additional riders encouraged to take transit because of City of Yes.

For example, stations on the R train in Bay Ridge, stations on the 2 and 5 trains in the Bronx, and most Staten Island Railway stations currently serve significantly fewer passengers today than they did five years ago. These stations and many others have previously provided service to significantly more people in the past than they do now and significantly more people than what can be expected from City of Yes. However, the MTA and City should continue monitoring ridership trends to determine which lines need increased service as housing is built. Ridership gains from City of Yes could help fill the gap between the capacity certain trains have and the current service they provide.

Potential Benefits for MTA Riders

As the MTA continues to work towards making 95% of its subway stations accessible, COY could provide a unique opportunity to bring its Zoning for Accessibility initiative into new developments around the city. This could be especially useful for new housing developments with large numbers of seniors or other people with mobility disabilities, so they can take full advantage of the systems at their front doors.

Beyond the reach of the subway, a large number of NYC neighborhoods, especially those in southeastern Brooklyn, eastern Queens, and Staten Island, rely primarily on local buses to get around and express busses to connect to jobs and schools in Manhattan. City of Yes poses an opportunity to not only evaluate the need for more service through additional ridership, but also an opportunity to revisit much of the physical infrastructure buses run on. To do this, the MTA would need to work closely with DCP and DOT to examine the changes to the street network that would be necessary to fulfill the potential for better bus transit, including fulfilling the mandates of the Streets Plan.

With development around the city that may fall just out of the bounds of Zoning for Accessibility, the city should explore expanding the program beyond the subway and encourage developers to fund improvements to bus shelters and infrastructure. Monitoring slow bus routes, especially those with the potential for additional ridership will determine how successful the MTA is at attracting new riders. The MTA will need close collaboration from city agencies and bus champions in city offices to make it happen.

The commuter railroads may also see an increase in ridership and financial benefits because of City of Yes, particularly in areas of Eastern Queens that will see a higher influx of new development. It is expected that new transit-oriented development could lead to increased ridership on the railroads within New York City, especially within the quarter mile zone where parking mandates will be eliminated. City of Yes is a golden opportunity to make the railroads more accessible to new and existing residents alike, through smart fare policy changes like expanding NYC’s Fair Fares program to the LIRR and Metro-North. PCAC analysis found that today 70% of the city’s 39 railroad stations are adjacent to census tracts where over 25% of residents are eligible for Fair Fares. The expansion of the program could cost as little as $5 million annually. Additionally, the MTA should address the lack of weekly unlimited options for the commuter rails within city limits. Creating a CityTicket Weekly option for fare payment that includes transfers to subways and buses would help residents afford the faster commutes that the commuter railroads have to offer. The MTA and City should take these factors into consideration in future fare changes and budget proposals to benefit new residents of all income levels.

Recommendations

- Continue to say “Yes” to transit-focused housing proposals like City of Yes. It is time for NYC to build housing that utilizes its greatest asset: the MTA. And in turn, the MTA can leverage the additional revenue to provide improved service, and therefore, encourage more housing that facilitates the housing of more people and higher ridership. Housing and transportation go hand in hand. Good housing policy is good transportation policy, and good transportation policy is good housing policy. The City Council was correct to pass City of Yes and should continue to support housing proposals that will help New Yorkers can reap the benefits of more housing near transit.

- The MTA should work hand in hand with DCP and DOT to fulfill the maximum benefits that City of Yes has the potential to bring, especially for bus riders. Targeted investments vis a vis the Streets Plan designed and built in cooperation between agencies can take advantage of newly created demand to deliver increased speed, reliability and pedestrian safety. Existing programs like Zoning for Accessibility should be expanded to bring tangible improvements to all riders.

- The MTA should monitor which subway, bus, or rail projects require capital investments in neighborhoods that see the highest growth from City of Yes in future capital plans. Assets could include new rolling stock, accessibility improvements in stations, or signaling upgrades to allow more frequent and reliable service on congested lines. These investments would complement the currently planned capital improvements that benefit neighborhoods that are expected to grow due to City of Yes, like signal upgrades on the A and C trains in eastern Brooklyn and southern Queens.

- Adjust service with revenue gained from additional ridership – anticipated at up to $309 million annually. Due to increased ridership created by new housing and residents, the MTA should explore using newly gained fare revenue to increase service, when needed. It should also consider improving its customer experience and operations, especially in areas that are likely to see a significant uptick in new residents outside of NYC’s core.

- Make paying the fare convenient and affordable on the commuter railroads by creating a weekly CityTicket with transfers to subways and buses and expanding Fair Fares to the rails within New York City. Up to 22,000 new affordable housing units could be built because of City of Yes, including in many neighborhoods in eastern Queens that are primarily served by the LIRR. Residents living in affordable housing are less likely to be able to easily afford full rail fares, let alone private automobiles that many of these neighborhoods are designed around. The city needs to meet transit-dependent residents’ needs with better, more affordable transit through discounted rail fare programs, including Fair Fares. Creating a weekly CityTicket with transfers to subways and buses would benefit frequent riders including residents living in transit-oriented developments near rail stations. It is important to create affordable options to entice and reward New Yorkers who rely on the rails for mobility and faster commutes.

Conclusion

New York City is defined by its density and transit – it’s what makes New York, New York. City of Yes builds on this region’s strengths and is designed for New York through and through.

More people living in housing that makes mass transit convenient means higher ridership for the subways and buses adding an additional as much as $309 million annually to the MTA’s operating budget via fare new collections. Higher demand for transit opens the doors for the MTA and other agencies to improve services and the rider experience. As the experts say, good housing policy is good transit policy, and good transit policy is good housing policy. This city requires visionary policy to address people’s housing and transit needs. City of Yes gets us there (and back home!), while increasing revenue to boot.

City of Yes opens the doors for improved transit opportunities but both City and State elected officials need to put in the work to realistically fulfill the transportation benefits that City of Yes can provide. Its time lawmakers show that the benefits of housing and transit are deeply intertwined.

Methodology

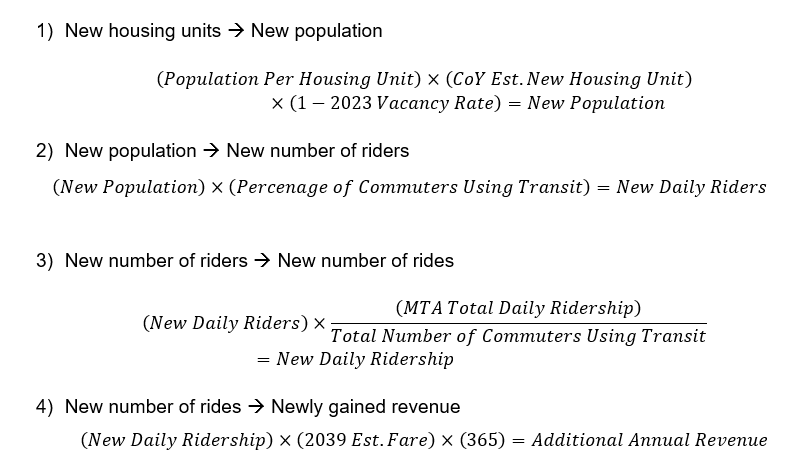

Under the assumption that an increase in total supply of housing within New York City’s boundaries would facilitate an increase in city population, it is possible to roughly compute the amount of transit ridership gained by the additional housing zoned by City of Yes when compared to no-action conditions. With forecasted ridership, it is possible to calculate forecasted revenue. The logic goes as follows:

Since City of Yes is a policy that covers the entire city, and not a specific site or neighborhood, it is appropriate to utilize city wide averages instead of comparatively more granular data. That data goes as follows:

Since City of Yes is a policy that covers the entire city, and not a specific site or neighborhood, it is appropriate to utilize city wide averages instead of comparatively more granular data. That data goes as follows:

Population per housing unit: 2.56 (NYC Department of City Planning, 2022).

Percent commute by transit 2023: 47.9% (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023).

2023 Vacancy rate: 1.4% (NYC Department of City Planning, 2022).

New housing from CoY: 58,000 – 80,000 (NYC Department of City Planning, 2023; Hochul, 2024).

MTA Daily ridership average across system: 4,987,001 (Metropolitan Transportation Authority, 2024).

Total number of commuters using transit daily average: 2,398,843 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023).

2039 estimated fare price: 3.95 (DiNapoli, 2022).

References

DiNapoli, T. (2022). MTA Budget Gaps Driven By Fare Revenue Drop. Retrieved from Office of the New York State Comptroller: https://www.osc.ny.gov/press/releases/2022/11/dinapoli-mta-budget-gaps-driven-fare-revenue-drop

Hochul, K. (2024). Governor Hochul, Mayor Adams and Council Speaker Adams Celebrate Passage of Most Pro-Housing Proposal in New York City History. Retrieved from Governor Kathy Hochul: https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-hochul-mayor-adams-and-council-speaker-adams-celebrate-passage-most-pro-housing#:~:text=As%20the%20city%20confronts%20a,critical%20infrastructure%20updates%20and%20housing.

Metropolitain Transit Authority. (2024). Subway and Bus Ridership for 2023. Retrieved from MTA: https://new.mta.info/agency/new-york-city-transit/subway-bus-ridership-2023

NYC Department of City Planning. (2022). NYC Population FactFinder. Retrieved from Department of City Planning: https://popfactfinder.planning.nyc.gov/

NYC Department of City Planning. (2023). City of Yes for Housing Opportunity Final Environmental Impact Statement. https://zap.planning.nyc.gov/projects/2023Y0427

U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce (2023). Census American Community Survey. Retrieved from Unites States Census: https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2023.S0801?q=commute

U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. (2023). Commuting Characteristics by Sex. American Community Survey, ACS 1-Year Estimates Subject Tables, Table S0801. Retrieved December 9, 2024, from https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2023.S0801?q=commute.