A Joint Report of RPA and the Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA (PCAC)

INTRODUCTION

In discussions about congestion pricing, some politicians and opponents of the policy have proposed exempting municipal workers from paying congestion pricing fees. This report finds that this is a lose/lose proposition. It would privilege municipal workers who drive over those who don’t and pit city employees against the rest of the workforce. It also results in substantial revenue losses and increased traffic congestion.

KEY FINDINGS

- Exempting municipal workers from congestion pricing will result in an annual loss of $140 million.

- A municipal worker exemption would increase tolls for everyone else: The $15 base toll would have to be increased to $17.45 to make up the loss and meet the revenue target.

- Municipal workers who drive to work earn, on average, $90,000/year, more than double the median income of New York’s labor force.

- NYPD, FDNY, and NYC DOE employees hold 106,554 parking placards around the city. Approximately 24,700 placards are held by employees of these three agencies whose primary work locations are in or near the Manhattan Central Business District. Exempting just this group would result in a loss of $71 million.

- Exempting municipal workers would continue to greenlight nearly 49,000 daily vehicle trips entering the zone, contributing disproportionately to GHG emissions and traffic. This, at a time when the city is recording the worst congestion and slowest traffic in years, and businesses and individuals are wasting time and fuel sitting in traffic.

- Municipal employees are already 78% more likely to drive to work than their private-sector counterparts, they are also more likely to drive for non-work trips.

- Exempting any subset of the workforce will open the floodgates to demands from other groups for exemptions as well. There is no defensible place to draw a line between who should be exempt and who should not.

- Exempting municipal workers is arbitrary and unfair to other workers who would see higher tolls as a result of the decision. For example, retail workers, nurses, orderlies, restaurant workers, janitorial staff, and many others across the Central Business District would still pay the toll.

- Exempting municipal workers could require a new environmental review process and would not deliver the promised congestion and pollution reduction goals.

- With traffic reductions due to congestion pricing, and a municipal employee exemption, City workers who use transit today may be induced to switch to driving.

- The majority of municipal workers– 75%– commute to jobs in the zone by transit. The best way to support them and other New Yorkers is by investing in transit.

- The congestion pricing pause is hurting transit riders by delaying meaningful investments to the transit system. Since the pause started in June, $330 million has been foregone.1

1As of 10/31/2024

Equity, Toll and Revenue Implications:

Our analysis reveals that municipal employees are 78% more likely to drive to work than their private-sector counterparts. They are also more likely to drive for non-work purposes. The greater probability of driving may be related to the availability of parking privileges and the higher than average incomes of municipal employees who drive to work in the CBD. Municipal workers who currently drive, earn, on average, more than double the city’s median income, and they earn almost 50% more than municipal workers who walk, bike, or use transit.

The charts below show the driving and non-drive percentages of private sector and municipal workers.

Table 1 shows the income differential of municipal workers who drive relative to their municipal counterparts in the same job titles who do not drive.

Table 1. Relative Incomes of Public Sector Workers who Drive and who Commute by Other Means

| Median Income of Manhattan Public Sector Workers | Drive | Other means |

| Police and Detectives | $110,000 | $70,000 |

| Teachers and Teaching Assistants | $70,000 | $61,000 |

| Post-secondary Teachers | $91,900 | $71,000 |

| Education Administrators | $172,000 | $102,000 |

| Transit Workers and Drivers | $99,000 | $70,000 |

| Nurses and Doctors | $80,000 | $95,000 |

| Firefighters | $100,000 | $120,000 |

| Janitors and Building Cleaners | $60,000 | $42,000 |

| Others | $75,000 | $66,000 |

| Average | $90,000 | $66,000 |

Given these data, a policy that exempts municipal workers from paying the congestion fee clearly favors the highest earning municipal workers.

We assume these workers are on-site at least four days per week, and they work 48 weeks per year. We assume a two-week vacation and ten federal holidays to arrive at the 48-week estimate. Given these assumptions, we estimate a revenue loss of $140 million or 14% of the legislated revenue target. Missing the target by this amount would mean a $2.1 billion shortfall to the capital plan. This shortfall to the legislated mandate would achieve the opposite effect of the stated goal of lowering tolls and helping those who can least afford the toll. It would require an additional toll increase to those who choose to drive. Furthermore, the exemption would be taxed as imputed income. Instead of paying the congestion fee and contributing to a better commute for everyone, exempt employees would have a higher tax bill.

Exempting municipal workers would also strongly damage the Congestion Pricing program’s ability to meaningfully reduce congestion. Municipal workers already benefit from parking privileges which are not available to the average New York worker; the benefit is conferred in the form of parking placards.

Currently, the city issues thousands of free parking placards to its employees, incentivizing them to drive. Employees of the three agencies that have been hypothetically elevated in the context of a municipal exemption, – NYPD, FDNY, and NYC Department of Education (DOE) – account for nearly 107,000 parking placards around the city, with almost 25,000 going to workers with primary work locations in or near the Manhattan CBD. While there is no current proposal on how this potential exemption would be implemented, based on the city’s long standing issue with parking placard abuse and lack of enforcement, it’s not unreasonable to be skeptical of the city’s ability to execute such an exemption. Fraudulent use of parking placards is well documented. It will be equally challenging to ensure that the congestion pricing exemption is actually used by the employee for commuting.

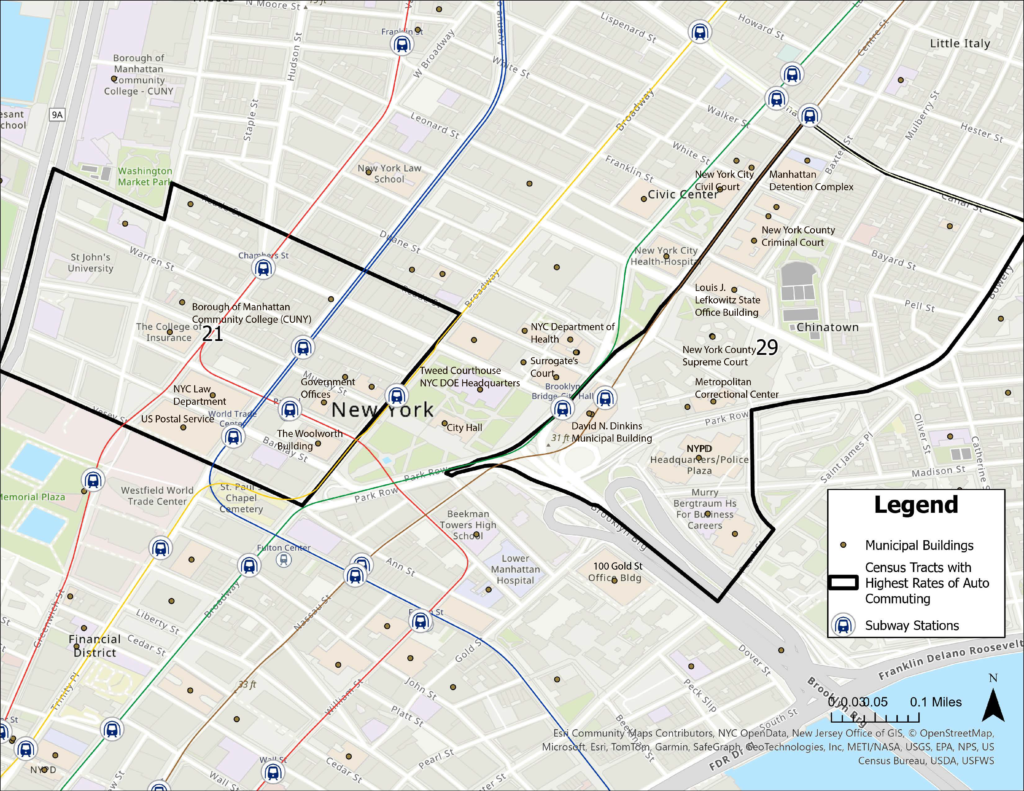

The two Census Tracts with the highest rate of auto commuting and the highest number of car commuters in the CBD are home to several municipal buildings in lower Manhattan. Census Tract 21 has the single highest rate of auto commuting in the CBD, despite it being one of the most transit-rich Census Tracts in the city. The Environmental Assessment for congestion pricing noted that:

“The availability of parking placards and/or free parking for some municipal employees likely contributes to the higher numbers of workers commuting by auto to Census Tract 21, rather than a business-specific need for personal automobiles.”

Chapter 6-54 of the CBDTP EA

Similarly, Census Tract 29 has the highest number of individual car commuters within the CBD. This tract contains many of the largest municipal buildings– including 1 Centre Street, the Jacob Javits Federal Building, and the NYPD Headquarters. Ultimately, exempting municipal employees – even if just from the three agencies who comprise a substantial portion of those driving into and working in these Census Tracts from congestion pricing, would fail to meaningfully reduce congestion in Lower Manhattan.

Census Tracts with High Rates of Car Commuting into the Manhattan CBD

TRAFFIC AND SOCIAL IMPACTS

In addition to the impacts on the cost of the toll on others, exempting municipal workers will also make congestion pricing less successful in other ways, impeding the goals of reducing congestion and improving traffic speeds for other drivers. Studies have shown that vehicle miles traveled are up 12% nationally since 2019, which mirrors the 14% increase in the New York City metro area. Even the total number of trips to the Central Business District, where vehicles are averaging a record low 4.8 mph2, have exceeded pre-COVID levels. Congestion pricing is anticipated to reduce congestion by 15%-20% in the Central Business District, helping to ease the approximately $20 billion in productivity lost to congestion annually in New York City. Any proposal to increase exemptions beyond those in the law endangers these benefits.

The environmental and public health impacts of congestion pricing will be blunted if we fail to attain the necessary trip and travel reduction because we have exempted such a significant portion of today’s drivers. Furthermore, if travel does become faster and more reliable, as predicted, that could be sufficient to entice municipal workers to drive who currently don’t. In the more than 120 days since congestion pricing was supposed to go into effect, nearly nineteen million car trips into the Central Business District that would have been deferred have been taken, resulting in over 850,000 tons of carbon dioxide emitted into the air. This undermines some of the core promises of the congestion pricing program, breaking trust with the electorate.

From an equity standpoint, the proposed municipal workers’ exception helping lower income New Yorkers who drive doesn’t hold up. According to the Community Service Society, a mission-driven organization that promotes equity and fights poverty, congestion pricing helps lower income New Yorkers far more than it harms. The very people the proposal purports to be defending are using transit much more than driving.

2 Analysis of NYC Traffic Congestion and Emergency Response Times (September 2024) Senator Brad Hoylman-Sigal and Sam Schwartz

FEDERAL APPROVAL AND FUNDING

The final tolling structure for congestion pricing was approved by the Traffic Mobility Review Board in November 2023 and then went through a rigorous reevaluation process by the MTA and the Federal Highway Administration, a process that took approximately seven months to complete. Exempting municipal employees would be a major change and would likely require a new review, thus adding further delay and expense to the start of the congestion pricing program and the projects it would fund. If the exemptions were coupled with additional changes to the tolling structure, such as lowering or increasing the fees, or additional exemptions, there is a significant chance that the entire current Environmental Assessment would need to be redone, adding multiple years of work and delaying the entire undertaking.

MOVING FORWARD

Even if municipal workers could be exempted without a lengthy renewed federal review/environmental assessment process, the burden on other drivers to reach the required revenue target would be prohibitive, at the same time that other critical components would be lost. A more cost-effective and transit-oriented approach would be for the Governor to provide municipal workers with free or reduced-cost OMNY cards and/or commuter rail passes, so they can simultaneously help reduce traffic, support the MTA’s operating budget, and help the state reach its ambitious climate goals. If the goal is to help the “little guy” then the way to do it is via transit investment. Unpausing the pause will then allow the program to proceed and an even greater majority of New Yorkers to benefit.

If the purpose is to improve air quality, raise money and mitigate congestion, there is no upside in exempting municipal workers.

METHODOLOGY

Our estimate of city workers who drive to work in the CBD is based on the Public Use Micro Sample of the US Census.

Our estimate of NYPD, FDNY, and DOE employees is based on PUMS, and a combination of City payroll data and the issuance of parking placards. In the latter case we estimate that 24,604 NYPD, FDNY, and NYC DOE workers drive into the CBD with essentially free-parking. We don’t know from the City’s data how many municipal employees drive and pay for their own parking.

Strategy 1: US Census

Using the Public Use Micro Sample of the US Census, we isolated the population identified as “local government employees” with workplaces in Manhattan. Based on the distribution of jobs in the Census Bureau’s 2021 Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics, we assume 80% work in the CBD.

Table M.1 shows the number of local government employees by job title who report driving to work in the CBD.

| Manhattan Public Sector Workers Who Drive by Occupation | |

| Police and Detectives | 11,370 |

| Teachers and Teaching Assistants | 6,139 |

| Post-secondary Teachers | 1,467 |

| Education Administrators | 1,150 |

| Transit Workers and Drivers | 2,974 |

| Nurses and Doctors | 2,464 |

| Firefighters | 1,279 |

| Janitors and Building Cleaners | 735 |

| Others | 21,114 |

| Total | 48,694 |

Assuming employees work in person 4 days per week and assuming a 48 week year (allowing for vacation and holidays), the loss due to this exemption would be over $140 million/year, or, approximately, 14% of the revenue to be generated.

The benefit accrues to the wealthiest employees, even within a job class as illustrated above.

All analysis flows from these facts.

Strategy 2: NYC Parking Placards

City agencies issue parking placards to some of their employees. Assuming placards are issued to employees who drive, placards serve as a proxy for the lower bound of municipal employees who drive for the three main city agencies that the Governor has proposed exempting from congestion pricing: teachers and administrators (NYC Department of Education, DOE), police officers and detectives (NYPD), and firefighters (FDNY). We assume some employees without placards also drive but we have no strategy to estimate how many, hence we do not estimate an upper bound. We assume the lower bound for further calculations.

Department of Education (DOE):

The DOE issued 62,294 placards to DOE employees; 9,227 are issued to people with work locations in the CBD, according to Citywide 2021 Payroll Data provided by the NYC Office of Payroll Administration and NYC Agency Authorized Parking Permit Data provided by the NYC Department of Transportation. This is shown in Table M.2.

Table M.2. NYCDOE Placards

| Total DOE Placards | DOE Placards for Districts 1-3 (districts that touch Manhattan CBD) | DOE placards for other employees working in Manhattan CBD | Total Manhattan Placards for DOE |

| 62,294 | 6,907 | 2,320 | 9,227 |

The New York Police Department also issues placards to some of its employees. The distribution of those working in Manhattan is shown in Table M.3.

Table M.3. NYPD Placards

| Total NYPD Placards | Rate of NYPD Employees Working in Manhattan | Total Manhattan Placards for NYPD |

| 31,325 | 41% | 12,843 |

Table M.4. FDNY Placards

The Fire Department of New York also issues placards to some of its employees. The distribution of those working in Manhattan is shown in Table M.4.

| Total FDNY Placards | Rate of FDNY Employees Working in Manhattan | Total Manhattan Placards for FDNY |

| 12,935 | 20% | 2,587 |

Total NYPD, FDNY, and DOE placards: 106,554

Total NYPD, FDNY, and DOE placards with primary work locations in Lower Manhattan: 24,657

Based on Citywide 2021 Payroll Data provided by the NYC Office of Payroll Administration and NYC Agency Authorized Parking Permit Data provided by the NYC Department of Transportation and 2024 NYC Department of Investigation Report on City-Issued Parking Placards

Financial impact of exempting FDNY/NYCDOE/NYPD employees from congestion pricing and exempting all municipal employees from congestion pricing, as a percent of total congestion pricing revenue:

| City Agency | Total Active Employee Placards | Placards Issued for Employees working in Manhattan CBD (estimate) | Revenue Loss (4 days/week, 48 weeks/year) | Percent of Total Revenue Lost with Exemption |

| NYPD | 31,325 | 12,843 | $36,987,840 | 4% |

| NYCDOE | 62,294 | 9,227 | $26,573,760 | 3% |

| FDNY | 12,935 | 2,587 | $7,450,560 | 1% |

| TOTAL | 106,554 | 24,657 | $71,012,160 | 7% |